Word for Microsoft 365 Word for Microsoft 365 for Mac Word for the web Word 2021 Word 2021 for Mac Word 2019 Word 2019 for Mac Word 2016 Word for iPad Word for iPhone Word for Android tablets Word for Android phones Word Mobile More. Less

This topic gives you step-by-step instructions and best practices on how to make your Word documents accessible and unlock your content to everyone, including people with disabilities.

You learn, for example, how to work with the Accessibility Checker to tackle accessibility issues while you're writing your document. You'll also learn how to add alt texts to images so that people using screen readers are able to listen to what the image is all about. You can also learn about how to use fonts, colors, and styles to maximize the inclusiveness of your Word documents before sharing them with others.

The following table includes key best practices for creating Word documents that are accessible to people with disabilities.

Avoid common accessibility issues such as missing alternative text (alt text) and low contrast colors.

Make it easy for everyone to read your documents.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way.

If you have to use tables, use a simple table structure for data only, and specify column header information.

To ensure that tables don't contain split cells, merged cells, or nested tables, use the Accessibility Checker.

Visually scan your tables to check that they don't have any completely blank rows or columns.

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table.

Use built-in headings and styles.

To check that the order of headings is logical, visually scan your document's table of contents.

To preserve tab order and to make it easier for screen readers to read your documents, use a logical heading order and the built-in formatting tools in Word.

You can also use paragraph banners to organize your content.

Include alt text with all visuals.

To find missing alt text, use the Accessibility Checker.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in images and other visuals.

Add meaningful hyperlink text and ScreenTips.

To determine whether hyperlink text makes sense as standalone information and whether it gives readers accurate information about the destination target, visually scan your document.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links.

Ensure that color is not the only means of conveying information.

To find instances of color-coding, visually scan your document.

People who are blind, have low vision, or are colorblind might miss out on the meaning conveyed by particular colors.

Use sufficient contrast for text and background colors.

To find insufficient color contrast, use the Accessibility Checker.

You can also look for text in your document that’s hard to read or to distinguish from the background.

If your document has a high level of contrast between text and background, more people can see and use the content.

Avoid writing important information in the Header or Footer sections of the document.

Headers and Footers are visible only in the Print Layout view and the Print Preview.

Double-click the Header or the Footer to activate and edit its content.

People who use screen readers miss out on important information as screen readers do not scan Headers or Footers.

Use built-in title, subtitle, and heading styles to include titles, subtitles, page numbers, and all other important information in the main body of the document.

Include any redundant information in the Header or Footer section.

The Accessibility Checker is a tool that reviews your content and flags accessibility issues it comes across. It explains why each issue might be a potential problem for someone with a disability. The Accessibility Checker also suggests how you can resolve the issues that appear.

In Word, the Accessibility Checker runs automatically in the background when you're creating a document. If the Accessibility Checker detects accessibility issues, you will get a reminder in the status bar.

To manually launch the Accessibility Checker, select Review > Check Accessibility. The Accessibility pane opens, and you can now review and fix accessibility issues. For more info, go to Improve accessibility with the Accessibility Checker and Check document accessibility.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way, like paragraphs with headings and banners. Tables with fixed width might prove difficult to read for people who use Magnifier, because such tables force the content to a specific size. This makes the font very small, which forces Magnifier users to scroll horizontally, especially on mobile devices.

If you have to use tables, use the following guidelines to make sure your table is as accessible as possible:

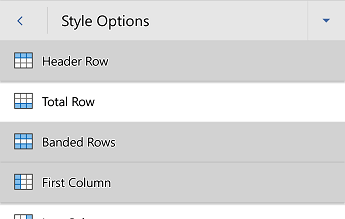

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table. Use a simple table structure for data only and specify column header information. Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

For step-by-step instructions on how to add a header row to a table, go to Create accessible tables in Word.

To ensure that tables don't contain split cells, merged cells, or nested tables, use the Accessibility Checker.

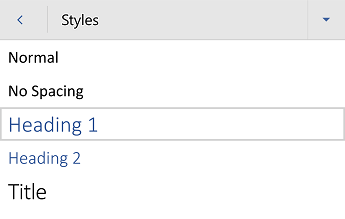

Title, Subtitle, and headings are meant to be scanned, both visually and with assistive technology.

Use the built-in Title and Subtitle styles specifically for the title and subtitle of the document.

Ideally, headings explain what a document section is about. Use the built-in heading styles and create descriptive heading texts to make it easier for screen reader users to determine the structure of the document and navigate the headings.

Organize headings in the prescribed logical order and do not skip heading levels. For example, use Heading 1, Heading 2, and then Heading 3, rather than Heading 3, Heading 1, and then Heading 2. Organize the information in your document into small chunks. Ideally, each heading would include only a few paragraphs.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to use the headings and styles, go to Improve accessibility with heading styles.

In addition to using headings to organize the content in your document, you can also create paragraph banners. In a paragraph banner, the background color block extends across the width of the document and highlights the text within the banner. This is a great alternative to tables to organize and separate content.

For instructions on how to create paragraph banners, go to Apply shading to words or paragraphs.

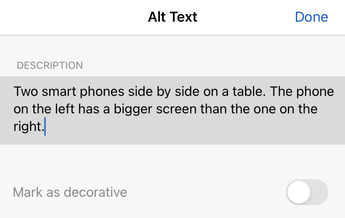

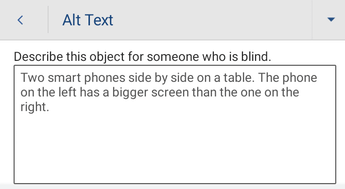

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in visual content. Visual content includes pictures, SmartArt graphics, shapes, groups, charts, embedded objects, ink, and videos. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention its intent. Screen readers read the text to describe the image to users who can’t see the image.

Avoid using text in images as the sole method of conveying important information. If you must use an image with text in it, repeat that text in the document. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention the existence of the text and its intent.

Tip: To write a good alt text, make sure to convey the content and the purpose of the image in a concise and unambiguous manner. The alt text shouldn’t be longer than a short sentence or two—most of the time a few thoughtfully selected words will do. Do not repeat the surrounding textual content as alt text or use phrases referring to images, such as, "a graphic of" or "an image of." For more info on how to write alt text, go to Everything you need to know to write effective alt text.

To find missing alt text, use the Accessibility Checker.

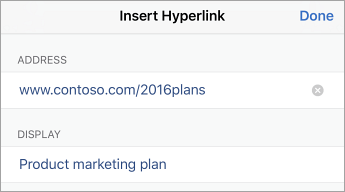

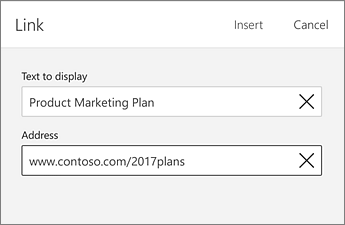

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links. Links should convey clear and accurate information about the destination. For example, avoid using link texts such as "Click here," "See this page," "Go here," or "Learn more." Instead include the full title of the destination page. You can also add ScreenTips that appear when your cursor hovers over text or images that include a hyperlink.

Tip: If the title on the hyperlink's destination page gives an accurate summary of what’s on the page, use it for the hyperlink text. For example, this hyperlink text matches the title on the destination page: Create more with Microsoft templates.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create accessible hyperlinks and ScreenTips, go to Create accessible links in Word and Create or edit a hyperlink.

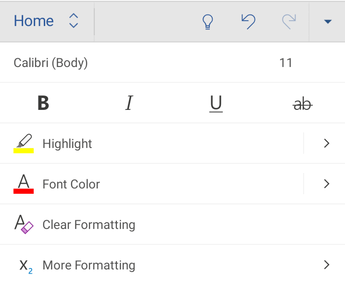

An accessible font doesn't exclude or slow down the reading speed of anyone reading a document, including people with low vision or reading disability or people who are blind. The right font improves the legibility and readability of the document.

For instructions on how to change the default font, go to Change the default font in Word.

Here are some ideas to consider:

if green is used to indicate “pass” and an uppercase X

The text in your document should be readable in a high contrast mode. For example, use bright colors or high-contrast color schemes on opposite ends of the color spectrum. White and black schemes make it easier for people who are colorblind to distinguish text and shapes.

Here are some ideas to consider:

To make it easier for screen readers to read your document, organize the information in your document into small chunks such as bulleted or numbered lists.

Design lists so that you do not need to add a plain paragraph without a bullet or number to the middle of a list. If your list is broken up by a plain paragraph, some screen readers might announce the number of list items wrong. Also, the user might hear in the middle of the list that they are leaving the list.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create lists, go to Create a bulleted or numbered list.

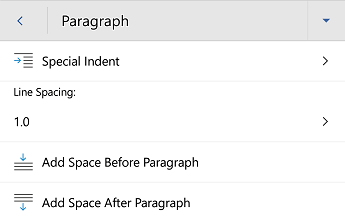

People who have dyslexia describe seeing text “swim together” on a page (the compressing of one line of text into the line below). They often see text merge or distort. To reduce the reading load, you can increase white space between sentences and paragraphs.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to adjust the spacing, go to Adjust indents and spacing in Word.

Try reading the document with Immersive Reader to check how it sounds like.

The following table includes key best practices for creating Word documents that are accessible to people with disabilities.

Avoid common accessibility issues such as missing alternative text (alt text) and low contrast colors.

Make it easy for everyone to read your documents.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way.

If you have to use tables, use a simple table structure for data only, and specify column header information.

To ensure that tables don't contain split cells, merged cells, or nested tables, use the Accessibility Checker.

Visually scan your tables to check that they don't have any completely blank rows or columns.

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table.

Use built-in headings and styles.

To check that the order of headings is logical, visually scan your document's table of contents.

To preserve tab order and to make it easier for screen readers to read your documents, use a logical heading order and the built-in formatting tools in Word.

You can also use paragraph banners to organize your content.

Include alt text with all visuals.

To find missing alternative text, use the Accessibility Checker.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in images and other visuals.

Add meaningful hyperlink text and ScreenTips.

To determine whether hyperlink text makes sense as standalone information and whether it gives readers accurate information about the destination target, visually scan your document.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links.

Ensure that color is not the only means of conveying information.

To find instances of color-coding, visually scan your document.

People who are blind, have low vision, or are colorblind might miss out on the meaning conveyed by particular colors.

Use sufficient contrast for text and background colors.

To find insufficient color contrast, use the Accessibility Checker.

You can also look for text in your document that’s hard to read or to distinguish from the background.

If your document has a high level of contrast between text and background, more people can see and use the content.

Avoid writing important information in the Header or Footer sections of the document.

Headers and Footers are visible only in the Print Layout view and the Print Preview.

Double-click the Header or the Footer to activate and edit its content.

People who use screen readers miss out on important information as screen readers do not scan Headers or Footers.

Use built-in title, subtitle, and heading styles to include titles, subtitles, page numbers, and all other important information in the main body of the document.

Include any redundant information in the Header or Footer section.

The Accessibility Checker is a tool that reviews your content and flags accessibility issues it comes across. It explains why each issue might be a potential problem for someone with a disability. The Accessibility Checker also suggests how you can resolve the issues that appear.

In Word, the Accessibility Checker runs automatically in the background when you're creating a document. If the Accessibility Checker detects accessibility issues, you will get a reminder in the status bar.

To manually launch the Accessibility Checker, select Review > Check Accessibility. The Accessibility pane opens, and you can now review and fix accessibility issues. For more info, go to Improve accessibility with the Accessibility Checker and Check document accessibility.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way, like paragraphs with headings and banners. If you have to use tables, use the following guidelines to make sure your table is as accessible as possible:

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table. Use a simple table structure for data only and specify column header information. Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

To ensure that tables don't contain split cells, merged cells, or nested tables, use the Accessibility Checker.

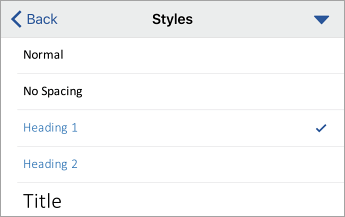

Title, Subtitle, and headings are meant to be scanned, both visually and with assistive technology.

Use the built-in Title and Subtitle styles specifically for the title and subtitle of the document.

Ideally, headings explain what a document section is about. Use the built-in heading styles and create descriptive heading texts to make it easier for screen reader users to determine the structure of the document and navigate the headings.

Organize headings in the prescribed logical order and do not skip heading levels. For example, use Heading 1, Heading 2, and then Heading 3, rather than Heading 3, Heading 1, and then Heading 2. Organize the information in your document into small chunks. Ideally, each heading would include only a few paragraphs.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to use the headings and styles, go to Improve accessibility with heading styles.

In addition to using headings to organize the content in your document, you can also create paragraph banners. In a paragraph banner, the background color block extends across the width of the document and highlights the text within the banner. This is a great alternative to tables to organize and separate content.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create paragraph banners, go to Apply shading to words or paragraphs.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in visual content. Visual content includes pictures, SmartArt graphics, shapes, groups, charts, embedded objects, ink, and videos. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention its intent. Screen readers read the text to describe the image to users who can’t see the image.

Avoid using text in images as the sole method of conveying important information. If you must use an image with text in it, repeat that text in the document. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention the existence of the text and its intent.

Tip: To write a good alt text, make sure to convey the content and the purpose of the image in a concise and unambiguous manner. The alt text shouldn’t be longer than a short sentence or two—most of the time a few thoughtfully selected words will do. Do not repeat the surrounding textual content as alt text or use phrases referring to images, such as, "a graphic of" or "an image of." For more info on how to write alt text, go to Everything you need to know to write effective alt text.

To find missing alt text, use the Accessibility Checker.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links. Links should convey clear and accurate information about the destination. For example, avoid using link texts such as "Click here," "See this page," "Go here," or "Learn more." Instead include the full title of the destination page. You can also add ScreenTips that appear when your cursor hovers over text or images that include a hyperlink.

Tip: If the title on the hyperlink's destination page gives an accurate summary of what’s on the page, use it for the hyperlink text. For example, this hyperlink text matches the title on the destination page: Create more with Microsoft templates.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create accessible hyperlinks and ScreenTips, go to Create accessible links in Word and Create or edit a hyperlink.

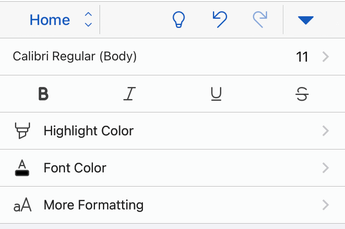

An accessible font doesn't exclude or slow down the reading speed of anyone reading a document, including people with low vision or reading disability or people who are blind. The right font improves the legibility and readability of the document.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to change the default font, go to Change the default font in Word.

Here are some ideas to consider:

if green is used to indicate “pass” and an uppercase X

The text in your document should be readable in a high contrast mode. For example, use bright colors or high-contrast color schemes on opposite ends of the color spectrum. White and black schemes make it easier for people who are colorblind to distinguish text and shapes.

Here are some ideas to consider:

To make it easier for screen readers to read your document, organize the information in your document into small chunks such as bulleted or numbered lists.

Design lists so that you do not need to add a plain paragraph without a bullet or number to the middle of a list. If your list is broken up by a plain paragraph, some screen readers might announce the number of list items wrong. Also, the user might hear in the middle of the list that they are leaving the list.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create lists, go to Create a bulleted or numbered list.

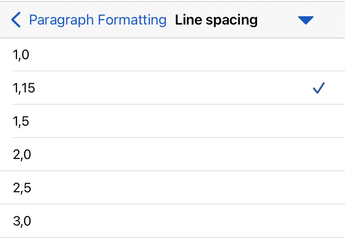

People who have dyslexia describe seeing text “swim together” on a page (the compressing of one line of text into the line below). They often see text merge or distort. To reduce the reading load, you can increase white space between sentences and paragraphs.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to adjust the spacing, go to Adjust indents and spacing in Word.

Try reading the document with Immersive Reader to check how it sounds like.

The following table includes key best practices for creating Word documents that are accessible to people with disabilities.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way.

If you have to use tables, use a simple table structure for data only, and specify column header information.

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells.

Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

Use built-in headings and styles.

To preserve tab order and to make it easier for screen readers to read your documents, use a logical heading order and the built-in formatting tools in Word.

Include alternative text (alt text) with all visuals.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in images and other visuals.

Add meaningful hyperlink text.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links.

Ensure that color is not the only means of conveying information.

People who are blind, have low vision, or are colorblind might miss out on the meaning conveyed by particular colors.

Use sufficient contrast for text and background colors.

If your document has a high level of contrast between text and background, more people can see and use the content.

Avoid writing important information in the Header or Footer sections of the document.

People who use screen readers miss out on important information as screen readers do not scan Headers or Footers.

Use built-in title, subtitle, and heading styles to include titles, subtitles, page numbers, and all other important information in the main body of the document.

Include any redundant information in the Header or Footer section.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way, like paragraphs with headings. Tables with fixed width might prove difficult to read for people who use Magnifier, because such tables force the content to a specific size. This makes the font very small, which forces Magnifier users to scroll horizontally, especially on mobile devices.

If you have to use tables, use the following guidelines to make sure your table is as accessible as possible:

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table. Use a simple table structure for data only and specify column header information. Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

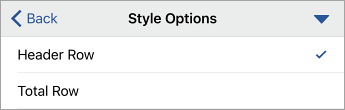

(Show ribbon). The Table tab opens. Select Style Options, and then select Header Row.

Title, Subtitle, and headings are meant to be scanned, both visually and with assistive technology.

Use the built-in Title and Subtitle styles specifically for the title and subtitle of the document.

Ideally, headings explain what a document section is about. Use the built-in heading styles and create descriptive heading texts to make it easier for screen reader users to determine the structure of the document and navigate the headings.

Organize headings in the prescribed logical order and do not skip heading levels. For example, use Heading 1, Heading 2, and then Heading 3, rather than Heading 3, Heading 1, and then Heading 2. Organize the information in your document into small chunks. Ideally, each heading would include only a few paragraphs.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in visual content. Visual content includes pictures, SmartArt graphics, shapes, groups, charts, embedded objects, ink, and videos. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention its intent. Screen readers read the text to describe the image to users who can’t see the image.

Avoid using text in images as the sole method of conveying important information. If you must use an image with text in it, repeat that text in the document. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention the existence of the text and its intent.

Tip: To write a good alt text, make sure to convey the content and the purpose of the image in a concise and unambiguous manner. The alt text shouldn’t be longer than a short sentence or two—most of the time a few thoughtfully selected words will do. Do not repeat the surrounding textual content as alt text or use phrases referring to images, such as, "a graphic of" or "an image of." For more info on how to write alt text, go to Everything you need to know to write effective alt text.

(Show ribbon). The relevant tab opens, for example, the Picture tab. Select Alt Text, and then type the alt text for the visual.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links. Links should convey clear and accurate information about the destination. For example, avoid using link texts such as "Click here," "See this page," "Go here," or "Learn more." Instead include the full title of the destination page.

Tip: If the title on the hyperlink's destination page gives an accurate summary of what’s on the page, use it for the hyperlink text. For example, this hyperlink text matches the title on the destination page: Create more with Microsoft templates.

An accessible font doesn't exclude or slow down the reading speed of anyone reading a document, including people with low vision or reading disability or people who are blind. The right font improves the legibility and readability of the document.

Here are some ideas to consider:

if green is used to indicate "pass" and an uppercase X

if red indicates "fail."

The text in your document should be readable in a high contrast mode. For example, use bright colors or high-contrast color schemes on opposite ends of the color spectrum. White and black schemes make it easier for people who are colorblind to distinguish text and shapes.

To make it easier for screen readers to read your document, organize the information in your document into small chunks such as bulleted or numbered lists.

Design lists so that you do not need to add a plain paragraph without a bullet or number to the middle of a list. If your list is broken up by a plain paragraph, some screen readers might announce the number of list items wrong. Also, the user might hear in the middle of the list that they are leaving the list.

People who have dyslexia describe seeing text “swim together” on a page (the compressing of one line of text into the line below). They often see text merge or distort. To reduce the reading load, you can increase white space between sentences and paragraphs.

When your document is ready, you can try a few things to make sure it is accessible:

The following table includes key best practices for creating Word documents that are accessible to people with disabilities.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way.

If you have to use tables, use a simple table structure for data only, and specify column header information.

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells.

Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

Use built-in headings and styles.

To preserve tab order and to make it easier for screen readers to read your documents, use a logical heading order and the built-in formatting tools in Word.

Include alternative text (alt text) with all visuals.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in images and other visuals.

Add meaningful hyperlink text.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links.

Ensure that color is not the only means of conveying information.

People who are blind, have low vision, or are colorblind might miss out on the meaning conveyed by particular colors.

Use sufficient contrast for text and background colors.

If your document has a high level of contrast between text and background, more people can see and use the content.

Avoid writing important information in the Header or Footer sections of the document.

People who use screen readers miss out on important information as screen readers do not scan Headers or Footers.

Use built-in title, subtitle, and heading styles to include titles, subtitles, page numbers, and all other important information in the main body of the document.

Include any redundant information in the Header or Footer section.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way, like paragraphs with headings. Tables with fixed width might prove difficult to read for people who use Magnifier, because such tables force the content to a specific size. This makes the font very small, which forces Magnifier users to scroll horizontally, especially on mobile devices.

If you have to use tables, use the following guidelines to make sure your table is as accessible as possible:

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table. Use a simple table structure for data only and specify column header information. Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

Title, Subtitle, and headings are meant to be scanned, both visually and with assistive technology.

Use the built-in Title and Subtitle styles specifically for the title and subtitle of the document.

Ideally, headings explain what a document section is about. Use the built-in heading styles and create descriptive heading texts to make it easier for screen reader users to determine the structure of the document and navigate the headings.

Organize headings in the prescribed logical order and do not skip heading levels. For example, use Heading 1, Heading 2, and then Heading 3, rather than Heading 3, Heading 1, and then Heading 2. Organize the information in your document into small chunks. Ideally, each heading would include only a few paragraphs.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in visual content. Visual content includes pictures, SmartArt graphics, shapes, tables, groups, charts, embedded objects, ink, and videos. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention its intent. Screen readers read the text to describe the image to users who can’t see the image.

Avoid using text in images as the sole method of conveying important information. If you must use an image with text in it, repeat that text in the document. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention the existence of the text and its intent.

Tip: To write a good alt text, make sure to convey the content and the purpose of the image in a concise and unambiguous manner. The alt text shouldn’t be longer than a short sentence or two—most of the time a few thoughtfully selected words will do. Do not repeat the surrounding textual content as alt text or use phrases referring to images, such as, "a graphic of" or "an image of." For more info on how to write alt text, go to Everything you need to know to write effective alt text.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links. Links should convey clear and accurate information about the destination. For example, avoid using link texts such as "Click here," "See this page," "Go here," or "Learn more." Instead include the full title of the destination page.

Tip: If the title on the hyperlink's destination page gives an accurate summary of what’s on the page, use it for the hyperlink text. For example, this hyperlink text matches the title on the destination page: Create more with Microsoft templates.

An accessible font doesn't exclude or slow down the reading speed of anyone reading a document, including people with low vision or reading disability or people who are blind. The right font improves the legibility and readability of the document.

Here are some ideas to consider:

if green is used to indicate “pass” and an uppercase X

The text in your document should be readable in a high contrast mode. For example, use bright colors or high-contrast color schemes on opposite ends of the color spectrum. White and black schemes make it easier for people who are colorblind to distinguish text and shapes.

Tip: To ensure that text displays well, select the Automatic setting.

To make it easier for screen readers to read your document, organize the information in your document into small chunks such as bulleted or numbered lists.

Design lists so that you do not need to add a plain paragraph without a bullet or number to the middle of a list. If your list is broken up by a plain paragraph, some screen readers might announce the number of list items wrong. Also, the user might hear in the middle of the list that they are leaving the list.

People who have dyslexia describe seeing text “swim together” on a page (the compressing of one line of text into the line below). They often see text merge or distort. To reduce the reading load, you can increase white space between sentences and paragraphs.

(More options). On the Home tab, select Paragraph Formatting.

When your document is ready, you can try a few things to make sure it is accessible:

The following table includes key best practices for creating Word for the web documents that are accessible to people with disabilities.

Avoid common accessibility issues such as missing alternative text (alt text) and low contrast colors.

Make it easy for everyone to read your documents.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way.

If you have to use tables, use a simple table structure for data only, and specify column header information.

To ensure that tables don't contain split cells, merged cells, or nested tables, use the Accessibility Checker.

Visually scan your tables to check that they don't have any completely blank rows or columns.

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table.

Use built-in headings and styles.

To check that the order of headings is logical, visually scan your document's table of contents.

To preserve tab order and to make it easier for screen readers to read your documents, use a logical heading order and the built-in formatting tools in Word for the web.

You can also use paragraph banners to organize your content.

Include alt text with all visuals.

To find missing alternative text, use the Accessibility Checker.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in images and other visuals.

Add meaningful hyperlink text and ScreenTips.

To determine whether hyperlink text makes sense as standalone information and whether it gives readers accurate information about the destination target, visually scan your document.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links.

Ensure that color is not the only means of conveying information.

To find instances of color-coding, visually scan your document.

People who are blind, have low vision, or are colorblind might miss out on the meaning conveyed by particular colors.

Use sufficient contrast for text and background colors.

To find insufficient color contrast, use the Accessibility Checker.

You can also look for text in your document that’s hard to read or to distinguish from the background.

If your document has a high level of contrast between text and background, more people can see and use the content.

Avoid writing important information in the Header or Footer sections of the document.

Headers and Footers are visible only in the Print Layout view and the Print Preview.

Double-click the Header or the Footer to activate and edit its content.

People who use screen readers miss out on important information as screen readers do not scan Headers or Footers.

Use built-in title, subtitle, and heading styles to include titles, subtitles, page numbers, and all other important information in the main body of the document.

Include any redundant information in the Header or Footer section.

The Accessibility Checker is a tool that reviews your content and flags accessibility issues it comes across. It explains why each issue might be a potential problem for someone with a disability. The Accessibility Checker also suggests how you can resolve the issues that appear.

In Word, the Accessibility Checker runs automatically in the background when you're creating a document. If the Accessibility Checker detects accessibility issues, you will get a reminder in the status bar.

To manually launch the Accessibility Checker, select Review > Check Accessibility. The Accessibility pane opens, and you can now review and fix accessibility issues. For more info, go to Improve accessibility with the Accessibility Checker and Check the accessibility of your document.

In general, avoid tables if possible and present the data another way, like paragraphs with headings and banners. If you have to use tables, use the following guidelines to make sure your table is as accessible as possible:

Screen readers keep track of their location in a table by counting table cells. If a table is nested within another table or if a cell is merged or split, the screen reader loses count and can’t provide helpful information about the table after that point. Blank cells in a table could also mislead someone using a screen reader into thinking that there is nothing more in the table. Use a simple table structure for data only and specify column header information. Screen readers also use header information to identify rows and columns.

To ensure that tables don't contain split cells, merged cells, or nested tables, use the Accessibility Checker.

Title, Subtitle, and headings are meant to be scanned, both visually and with assistive technology.

Use the built-in Title and Subtitle styles specifically for the title and subtitle of the document.

Ideally, headings explain what a document section is about. Use the built-in heading styles and create descriptive heading texts to make it easier for screen reader users to determine the structure of the document and navigate the headings.

Organize headings in the prescribed logical order and do not skip heading levels. For example, use Heading 1, Heading 2, and then Heading 3, rather than Heading 3, Heading 1, and then Heading 2. Organize the information in your document into small chunks. Ideally, each heading would include only a few paragraphs.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to use the headings and styles, go to Improve accessibility with heading styles.

In addition to using headings to organize the content in your document, you can also create paragraph banners. In a paragraph banner, the background color block extends across the width of the document and highlights the text within the banner. This is a great alternative to tables to organize and separate content.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create paragraph banners, go to Apply shading to words or paragraphs.

Alt text helps people who can’t see the screen to understand what’s important in visual content. Visual content includes pictures, SmartArt graphics, shapes, groups, charts, embedded objects, ink, and videos. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention its intent. Screen readers read the text to describe the image to users who can’t see the image.

Avoid using text in images as the sole method of conveying important information. If you must use an image with text in it, repeat that text in the document. In alt text, briefly describe the image and mention the existence of the text and its intent.

Tip: To write a good alt text, make sure to convey the content and the purpose of the image in a concise and unambiguous manner. The alt text shouldn’t be longer than a short sentence or two—most of the time a few thoughtfully selected words will do. Do not repeat the surrounding textual content as alt text or use phrases referring to images, such as, "a graphic of" or "an image of." For more info on how to write alt text, go to Everything you need to know to write effective alt text.

To find missing alt text, use the Accessibility Checker.

People who use screen readers sometimes scan a list of links. Links should convey clear and accurate information about the destination. For example, avoid using link texts such as "Click here," "See this page," "Go here," or "Learn more." Instead include the full title of the destination page. You can also add ScreenTips that appear when your cursor hovers over text or images that include a hyperlink.

Tip: If the title on the hyperlink's destination page gives an accurate summary of what’s on the page, use it for the hyperlink text. For example, this hyperlink text matches the title on the destination page: Create more with Microsoft templates.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create accessible hyperlinks and ScreenTips, go to Create accessible links in Word and Create or edit a hyperlink.

An accessible font doesn't exclude or slow down the reading speed of anyone reading a document, including people with low vision or reading disability or people who are blind. The right font improves the legibility and readability of the document.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to change the default font, go to Change the default font in Word.

Here are some ideas to consider:

if green is used to indicate “pass” and an uppercase X

The text in your document should be readable in a high contrast mode. For example, use bright colors or high-contrast color schemes on opposite ends of the color spectrum. White and black schemes make it easier for people who are colorblind to distinguish text and shapes.

Here are some ideas to consider:

To make it easier for screen readers to read your document, organize the information in your document into small chunks such as bulleted or numbered lists.

Design lists so that you do not need to add a plain paragraph without a bullet or number to the middle of a list. If your list is broken up by a plain paragraph, some screen readers might announce the number of list items wrong. Also, the user might hear in the middle of the list that they are leaving the list.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to create lists, go to Create a bulleted or numbered list.

People who have dyslexia describe seeing text “swim together” on a page (the compressing of one line of text into the line below). They often see text merge or distort. To reduce the reading load, you can increase white space between sentences and paragraphs.

For the step-by-step instructions on how to adjust the spacing, go to Adjust indents and spacing in Word.

Try reading the document with Immersive Reader to check how it sounds like.